Note:

This page refers specifically to the MIPS-flavoured Assembly Language. Click here to read more about the MIPS (Architecture). Alternatively you can also read about x86 assembly.

What?

It’s an (extremely low-level) programming language that corresponds closely to the commands of an ISA (Instruction Set Architecture). As such programming language, it’s human readable. The mapping from MIPS (Architecture) and MIPS Assembly Language is 1-1. What does that mean? At the end of the day, the (ISA) instructions you feed into a computer are just 1s and 0s. Assembly is a symbolic representation of MIPS which is a representation of machine instructions.

The Assembler:

The rest of this page is the syntax and how to code the coding language. But how do we actually convert the “human readable” (it’s still fucking hard to understand) coding language into machine code - 1’s and 0’s? That’s the assembler.

Instruction Breakdown:

- R-Type:

operator $destination, $source1, $source2- EG:

add $t0, $t1, $t2 # $t0 = $t1 + $t2

- EG:

- I-Type:

operator $destination, $source, immediate- EG:

addi $t0, $t1, 5 # $t0 = $t1 + 5

- EG:

- Memory Access:

operator $destination/source, offset($base)- EG:

lw $t0, 4($t1) # Load word from address ($t1+4) into $t0 - EG:

sw $t0, 8($t1) # Store word from $t0 to address ($t1+8)

- EG:

Note on BEQ $address works:

Note on how

BEQregisters workWhen BEQ has a label, it’s actually how many instructions away from the current instruction it is (i.e. 3 instructions down). To get the byte address, we left shift it by 2 (i.e. multiply it by 4 to get its byte address from the current spot).

Note on how j-type instructions work:

Unlike BEQ, j-type contain the absolute address

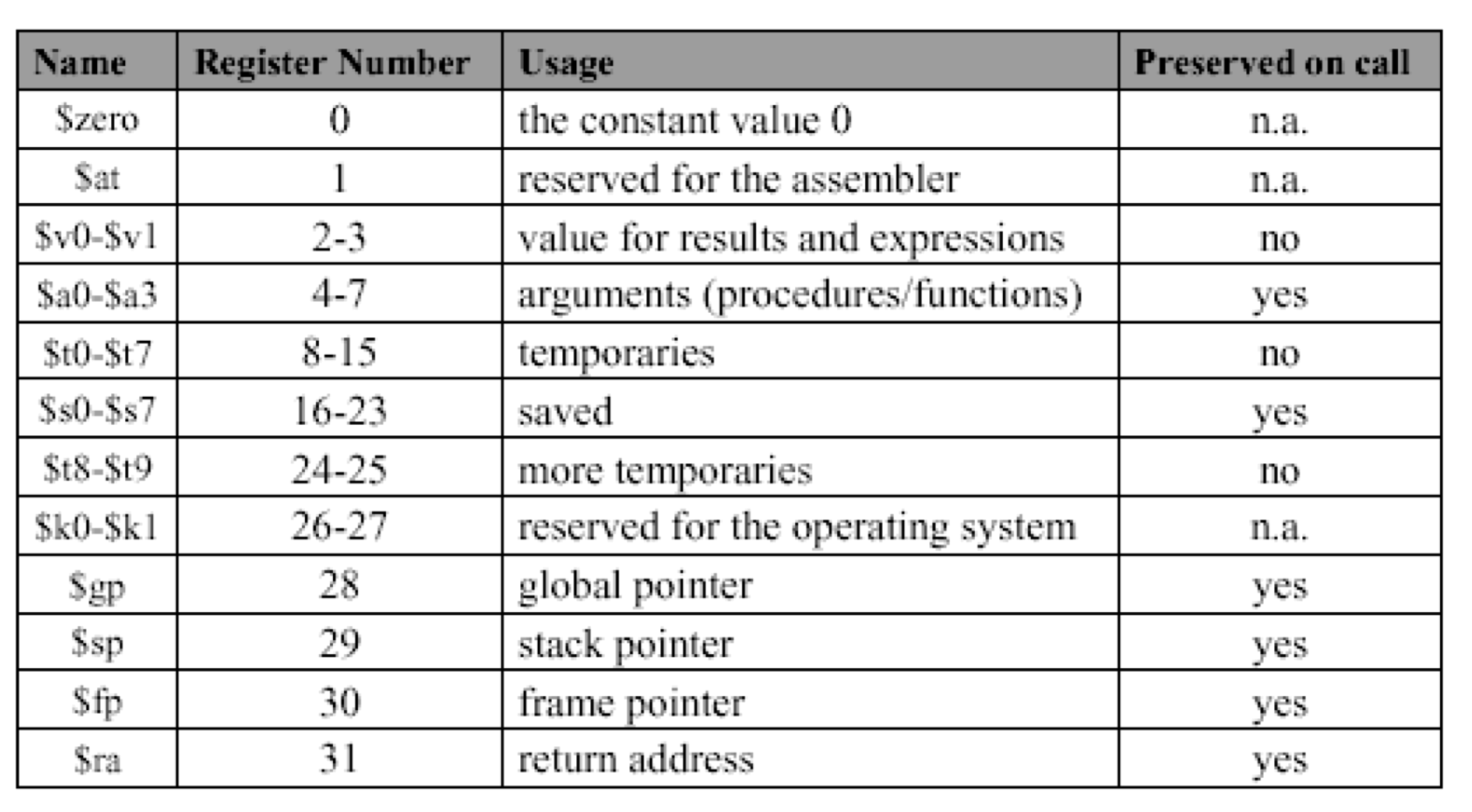

Registers Conventions

- Program variables are held in $s0-$s7

- Temporary variable es inside a method call: $t0-$t9

- Registers $a0-$a3 are used for passing arguments into functions.

- Register $zero is legit hardwired to 0

- There’s a Program Counter (PC). This literally just keeps track of the instruction to execute for the CPU

- There’s other special ones lol.

- Also check this conversation for a better idea.

Operating on stuff > 32 bits?

If you have a list and are reading in billions of entries, you can’t store those in Registers. Instead, you store them in memory. The way to transfer the two? Data Transfer Instructions. You can store an array’s memory’s address into the register.

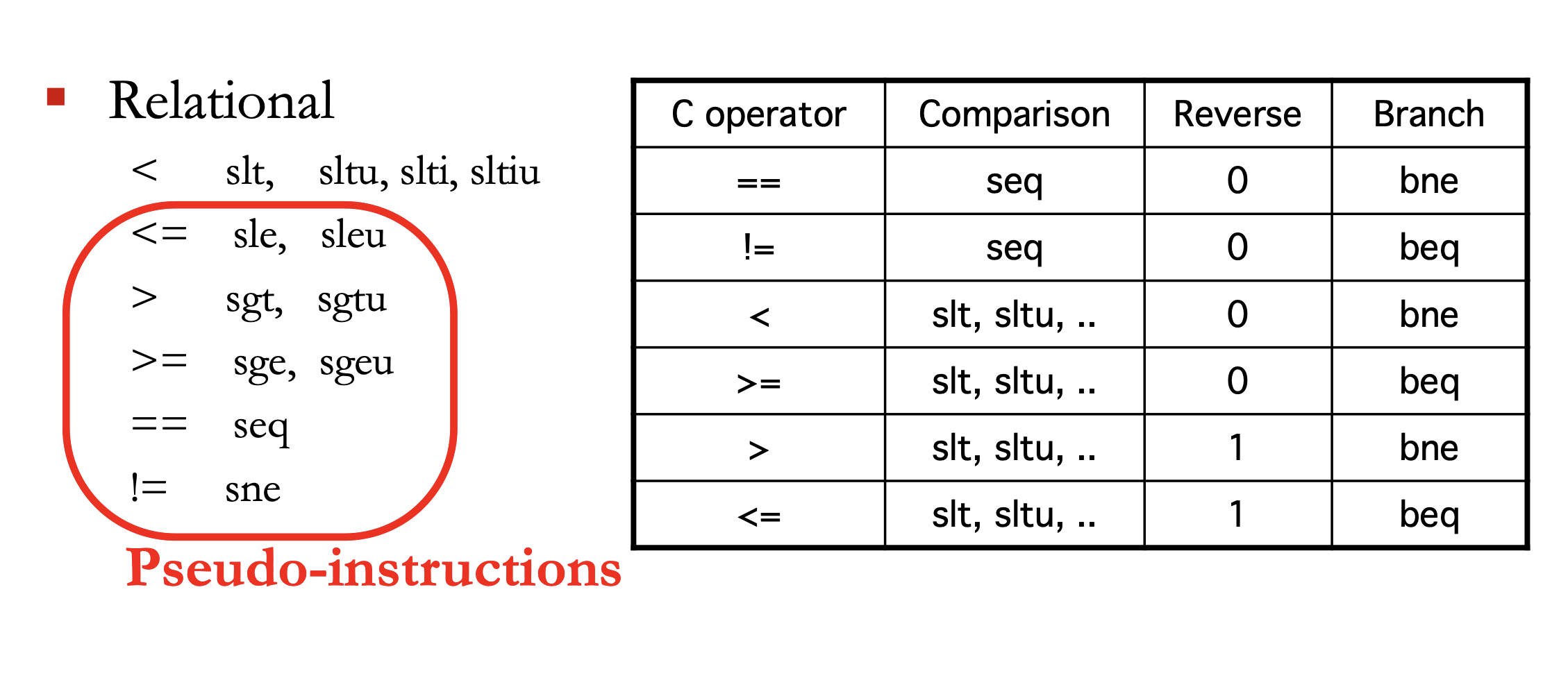

Set if Less Than (SLT), Branch if EQual (BEQ):

You can use the following keywords to perform basic comparisons:

- SLE - Set if Less or Equal to

- SGT - Set if Greater Than

- SGE - Set if Greater than or Equal to

- SEQ - Set if EQual to

- SNE - Set if Not Equal to

Assembly Example:

slt $t0, $s0, $s1 # Sets t0 to 1 if true, else to 0 if not.

beq $t0, $zero, l1 # If above was set to 0, jump to L1

and $s3, $s2, $s1 # Perform bitwise AND

j l2

l1: or $s3, $s2, $s1 # Perform bitwise OR

l2:Method Calls:

In Python or Java, there’s the ability to declare a function somewhere and call it somewhere else. MIPS (Architecture) does this in a roundabout way.

We use jal label to Jump-And-Link to a specific label. The use of the And-Link bit? It sets $ra to where you were before you left jumped. Then, whenever you want to return to wherever you were before the method call, simply run jr ra.

Convention for ‘Method Calls’:

The following isn’t true in MIPS by default. We have to write the code so that it is.

- Typically store ‘parameters’ to $a0 - $a3

- Typically store ‘return values’ to v1

- Registers s7 are stored across call boundaries.

- Registers t9 aren’t stored across call boundaries.

The Stack Within MIPS:

Thestack is a concept that’s incredibly useful within MIPS. It’s also fairly complicated. Read more about it in The Stack’s Use in MIPS